Pacioli, da Vinci, and the Account of Time for the Age of Quantum Computing

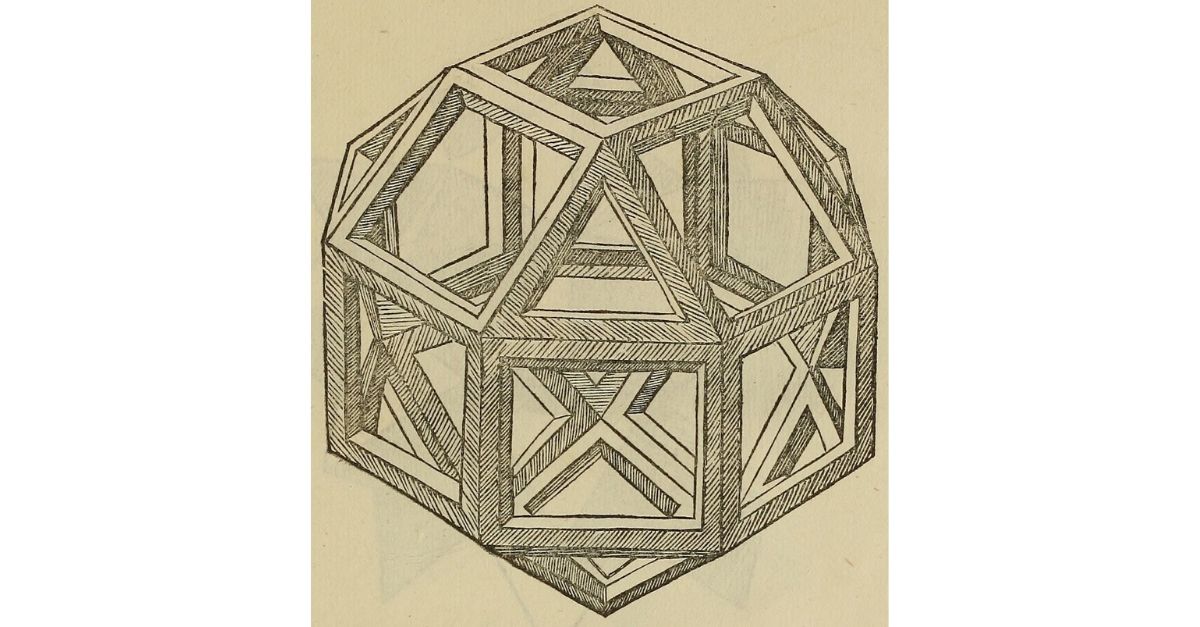

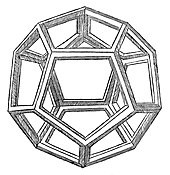

Illustration by Leonardo da Vinci from Luca Pacioli’s “De divina proportione”

On the necessity of creativity:

“Some people do believe Earth is flat. Others say the universe is 6000 years old… It is tempting to say that’s their problem, not science’s. But science is also limited in what it can say. It can’t prove a negative: there might be dragons and unicorns, a monster in Loch Ness, a God. It can’t even be definitive about all the positives. “Our evidence may at times leave us able to make only probabilistic judgements – we may sometimes be restricted to saying that a certain outcome or theory is likely to be true,” says Jennifer Nagel [philosopher] at the University of Toronto, Canada.“

Inside Knowledge: What makes scientific knowledge special, by Michael Brooks, New Scientist

A recent posting on this site, “Spending Time’s Currency Well”, advanced the notion that each of us is born with an unknowable quantity of time to spend, like a currency, until we reach our inevitable physical limit.

To the extent that our social interactions allow, we can spend our time as we believe best to achieve our desires. The specific desires that drive each one of us through time will vary over time, but perhaps ultimately as philosopher Rebecca Goldstein put it, “we are beings of matter who long to matter” and our motivation is to make a difference in the flow of time.

We are now defining a pivotal point in time, with our technology about to achieve such speed, accuracy, and reach into our lives as to challenge the human mind’s creative capacity and our individual ability to make a difference in the flow of time. It may be a common assumption that technology will inevitably reign supreme, because we have no means of upgrading the brain’s processing speed and accuracy at the same rate that we can add power and memory to computers. But is obsolescence of the mind necessarily a foregone conclusion?

Can we reserve a place in our technological algorithms for the creative potential of the human mind, to preserve our individual and collective capacity to make a difference in the passage of time from past to present that will resonate into the future – before the brief moment of the present slips from our grasp and retreats into the past?

I have described The Center for Humane Technology and its Ledger of Harms initiative as being particularly important in the present moment, as humanity is about to embark on perhaps its most significant technological advance, that of the quantum computing revolution. An earlier posting on this site briefly outlined the nature of quantum computers and the particular challenge that they will pose for financial reporting.

The potentially infinite speed of quantum computers (according to the U.S. government’s National Institute of Standards and Technology) will derive from their ability to transmit data in superposition of the universal minimum bit, the quantum. In other words, instead of a signal flowing from an “on” (or beginning) state to an “off” (or ending) state with some time delay in the process, as signals now do in traditional binary computers, quantum computers use the physics of quantum entanglement to produce signals that are simultaneously on and off.

In superposition, the quantum signal’s past will intersect with its future – and where does that leave us in the present, that moment in time that delivers to us our creative opportunity to make a difference in time?

The challenge in the bits and bytes of quantum computing will go beyond accounting and extend into every human interaction that is facilitated by the quantum computer. How will we know the beginning and the end of each transaction, when all transactions are simultaneously on and off? How will we be able to distinguish between cause and effect in any transaction, and the sequencing of cause and effect in multiple transactions, so that we can understand our trajectory in the flow of time relative to our individual desires? In superposition, the quantum signal’s past will intersect with its future – and where does that leave us in the present, that moment in time that delivers to us our creative opportunity to make a difference in time?

If you think the quantum computing revolution is a far-in-the-future dream, stop to consider Google’s claim last October to have achieved “quantum supremacy”. It was reported that the quantum computer Google is developing was able to complete a calculation in seconds that would have required the world’s fastest binary supercomputer 10,000 years to perform. While IBM contests the 10,000-year estimate and believes its best binary machine could perform the calculation in 2.5 days and more accurately than Google’s machine, the latter’s speed advantage would still be considerable – and some might argue worth a reduction in accuracy. Other companies are in the quantum race too; on March 3, Honeywell announced it has developed a quantum machine that is capable of processing conditional statements. The quantum revolution will be here sooner than we imagine, and even if it takes more time the principle of Pascal’s wager indicates prudence in preparing for its benefits – and its harms – with all due speed and attention.

Technology and time

The Center for Humane Technology was founded by Tristan Harris, a being of matter whose longing to matter in a meaningful and beneficial way to all of us is clear to witness. His longing motivated my writing “Spending Time’s Currency Well”, as an echo of the public call that Tristan made in 2016 for “Time Well Spent” after resigning his job as a design ethicist for Google. The Center’s Ledger of Harms initiative is intended to measure what the Center describes as “the large-scale negative impacts of attention-grabbing business models”.

We can and should debate the nature and attributes of existing and emerging technologies, in order to agree on and then continually re-evaluate what we consider to be “humane”, because it is a term that takes on different meanings in different times. Without doubt there will be many and varying interpretations of “humane”, but at its root is the word “human” and the implication of the potential for time that resides in you and me, in each of the other 7.4 billion humans who presently share planet Earth, and in the countless human generations who will succeed us in the future. Together we have such great potential to resonate through time.

Anything that harms human potential harms each one of us in the present, and diminishes our future probabilities and those of the generations who will follow. When there is agreement on the harms to human potential, they can be listed in one column of the Ledger of Harms. Every ledger has two opposite columns that balance to zero in the middle, and so with the harms to human potential recorded on one side we will find balance in the ledger by listing the benefits to human potential on the opposite side. The challenge will be to agree on that which separates harm from benefit, but it seems natural that beings of matter who long to matter would do so. We would do it not just for our own benefit, but for the benefit of our children who depend on us as much as we were once in their position and utterly dependant on those who preceded us in time.

But when technology is applied to destructive purposes, whether in the form of warfare or environmental destruction or the spread of fear, there is great potential for harm… Understanding the potential for harm, and deciding to act in a way that avoids harm, requires time.

To be sure, rapid developments in technology have brought many benefits to the present. Technology has brought tremendous advances to science – for example in our ability to observe the stars and planets and the black hole at the centre of our own galaxy, and to explore more deeply the quantum physics of the universe. Technology has helped us to bring many once deadly diseases under control, and has contributed to a widespread distribution of knowledge and a reduction in poverty. But when technology is applied to destructive purposes, whether in the form of warfare or environmental destruction or the spread of fear, there is great potential for harm.

Understanding the potential for harm, and deciding to act in a way that avoids harm, requires time. Before it can logically determine an action or reaction in the present, the human mind requires time in order to reflect on and to compute the full range of probabilities that may follow in the future. In a universe of uncertainty, how else could we render any logical decisions in pursuing our desires without having first taken even the briefest pause for reflection? As much as it is challenged by algorithmic speed, time for reflection is essential in a universe of uncertainty.

Uncertainty is guaranteed by universal physics: the more we know our position in space and time the less we know our momentum, and vice versa – this is the basis of physicist Werner Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle. As much as we might fear uncertainty, it exists as a logical necessity in a universe that can be shaped by the varying desires and the dynamic potential of beings of matter such as you and me. A universe that offered only certainty of outcomes would be static. Uncertainty allows for you to be different from me and from everyone else and for each of us to retain our own creative capacity. And so it is both our challenge and our potential to chart a course through time without absolute knowledge of every future destination in our journeys.

Navigating uncertainty requires time for reflection, but to deliver great speed today’s algorithms are designed to eliminate reflection. Algorithms are programmed to receive inputs in the form of electrical signals on which they perform specific sequences of calculations to generate the outputs intended by the human programmers. Unless an algorithm is specifically designed to require human intervention – such as a social media algorithm that seeks human input in the form of a “like” – algorithms process continuously, without stopping.

Continuous processing is what makes algorithms so fast and maybe this would be ideal if the programmers of the algorithms were perfect beings with perfect intentions, but the fact is that we all make mistakes and we all have the capacity to learn from mistakes. Neither you nor I nor the programmers nor their masters are exempt from these human traits. I have made many errors in my own life that I have later regretted, but errors and regret motivate me to better paths and sometimes to the greatest gift of all which is the grant of forgiveness for the injuries I have caused to others. Learning and forgiveness are the rewards of joy that make the examined life worth living. For a wonderfully concise, impressive, and philosophical reflection on the history of data science and errors of unintended consequences, I recommend unreservedly Hector Levesque’s Common Sense, The Turing Test, and the Quest for Real AI.

Having now defined the present pivotal point in time, we might ask what room will be left to correct programming errors and unintended consequences at the speed with which continuously processing algorithms will soon operate? If current trends continue, algorithms will soon achieve the potential to shape the flow of time, leaving humans little or no capacity to influence the direction of time’s arrow.

After we are overwhelmed by algorithmic speed, how will conscious beings of matter like you and I ever achieve our longing to matter and to make a difference in time? What will motivate us, after we cede our capacity to define the present to the algorithms and their speed and convenience? Will we have time to impress our creative potential in the present, before the outcomes of action and reaction become unchangeable and what we called the present becomes the past and is replaced by more of the same? As time moves to the future with a trajectory that can never be fully known, in every moment that we arrive at the present what meaning would be left for each of us to derive and to project our understanding of time?

Past, present, and future in the account of the reasons why

To make a difference in time is to add meaning, by altering the course of events in the present with our actions and reactions, and after physical existence ends by the memories that we leave behind to motivate successive generations. As Carlo Rovelli explains in his Order of Time, the word “time” is derived from the word for division and so time is a unity that is divided into events. An event is defined in the present, when action and reaction combine to form an outcome of probability that adds to the story of time. The story of time is what we call history. Often the consequences of an event in time are minimal and sometimes they are momentous, but within this range we can be sure that any event adds at minimum some consequences to history. Who among us would wish to be powerless in the writing of time’s story, whether in our own family and social orbits or in a broader context of any magnitude?

If our task in life is to navigate time and to spend time’s currency well in rendering our accounts, then history’s signals are important guides to navigation and to our contribution however great or small to history’s flow.

Before I became a financial accountant I obtained my degree in history, which is another form of account. History is the account of time that flows only one way from cause to effect, with the unchangeable past delivering to the present a message or signal that explains the connections of sequences of events and provides the reasons why time and space have come to be the way they now are. History’s signals are sometimes wonderful and sometimes horrifying, but always enlightening, accounts of time. History will include the outcomes of the actions and reactions that you or I take, which are reflections of our individual accounts of time. If our task in life is to navigate time and to spend time’s currency well in rendering our accounts, then history’s signals are important guides to navigation and to our contribution however great or small to history’s flow.

Plato was a great philosopher and geometer who called the present a “state of coming to be”, a fluid state of dynamic potential that stands in the middle of past and future and divides the former from the latter. It is only in the present, after all, that we can make a difference in time’s flow. There is much geometry that the philosopher employs to describe the flow of time. And when you think about it, geometry and time appear to have much in common. Certainly the physical universe is fundamentally geometric and symmetric, as we know well from the discoveries and creativity of Pythagoras, Euclid, Galileo, Euler, Newton, Maxwell, Gauss, Riemann, Boltzmann, Heisenberg, Noether, Einstein, and many other scientists. Both geometry and time are perfections of connection and neither allows for arbitrary breaks in its combinations. Geometry, like time, is always logical and never random in its connections. Just as surely as geometric edges connect to vertices that connect a face area – whether in a simple geometric figure or in the multi-dimensional complex geometry of the universe – science has detected no illogical connections in the flow of time from past to future over the course of the 13.8 billion years that the universe has existed to present. Time’s connection of past to future never fails to deliver us safely to its middle ground, to the present where individually and collectively we set our course in time. Beings of matter who long to matter wouldn’t wish for it to be any other way.

The same philosopher geometer who wrote of the present as a state of coming to be also wrote that knowledge is “the account of the reasons why”. In the account of the reasons why we find an understanding of the sequences of events that have brought us to the present, when we are poised for action and reaction with the guidance of wisdom and virtue. As surely as the universe is logical in its physical geometry, so surely must be the account of the reasons why.

It may help to understand the account of the reasons why as the continual account of time’s events that we make in our minds and that guides the exercise of our belief in the present. In a universe of uncertainty, none of us is able to foretell with complete accuracy the chain of all future outcomes of any of our actions and reactions as they ripple through time and affect the motivations of others. But informed with the account of the reasons why, a being of matter who longs to matter is capable of logical prediction and can act with a measure of confidence that the action or reaction under contemplation will produce desired outcomes.

Luca Pacioli, Leonardo da Vinci, and the geometry of time

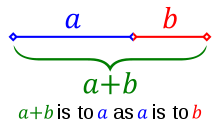

Readers of the home page essay “Belief and Accounting” and of my other blogs will know how passionate I am about the secret and meaning that Luca Pacioli embedded in the two words debit and credit. Debit means belief owed and credit means belief received, each being half of the story that belief makes. Debits and credits are equal and opposite reflections of belief, and belief is always in the middle of their combined focus. Over time for each economic actor, debits and credits accumulate in differing ratios to form what accountants call “equity”. Equity, which is the difference between what an individual or business has received and owes, is measured in tokens of belief called currency and units of currency are the basis of all financial accounts across the world.

Belief, Pacioli knew, is a fundamental requirement of making a difference in time in the present. Pacioli was a careful reader of the dialogues of the philosopher geometer, and decoded the geometric clues that he discovered in Plato’s writings to apply them to the invention of double entry accounting. In its measurement of equity, Pacioli’s double entry system provides us with an account of binary transactions in time, with unbroken geometry from cause to effect, beginning to end, and input to output. His system has survived for five centuries and shows no potential for failure in the ability of debit and credit to form a complete account of the uncertain flow of belief that always balances to zero.

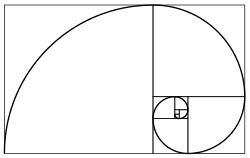

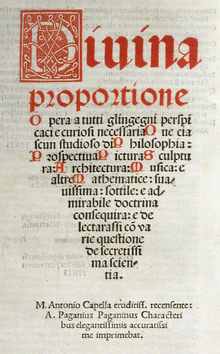

Pacioli was a brilliant mathematician and geometer, both of which are on display in his masterpiece the Divina Proportione, on the mathematics and geometry of the golden ratio. You can gaze on the brilliantly-illustrated work here, courtesy of the Institute of Chartered Accountants of England, Scotland and Wales.

It is not widely known that Pacioli’s student, while they both lived from 1496-1499 at the Corte Vecchio in Milan under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, was Leonardo da Vinci. In Leonardo, Luca was fortunate to have had both a student and a friend whose genius continues to resonate through time to today and doubtless to the years and centuries that will follow. During a visit to Florence and Milan I had the incredible fortune to see in two exhibits the brilliance of Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook diagrams on fluid dynamics and on mechanics. There is a timelessness in da Vinci’s drawings, in his delicately-drawn lines and the thought he applied in the integration of the lines to demonstrate the wonders of physics and geometry.

Why did Luca and Leonardo hide the secret science and mysteries of harmonic forms, and what clues did they provide to deliver a message through time about geometric probabilities in a universe of uncertainty?

Having witnessed the output of one of history’s most creative geniuses with my own eyes, the mind was led to imagine the wonders that Leonardo and Luca would, beyond a shadow of a doubt, have conjured during their collaboration five centuries ago. Leonardo provided sixty drawings of the solids that appear at the end of Luca’s manuscript. That the two collaborators did not reveal the full story of their discoveries I am sure. Pacioli himself hinted at this in writing in the first page of the Divina Proportione of his promise to deliver both “A work necessary for all the clear-sighted and inquiring human minds …” and “…delight in diverse questions touching upon a very secret science” through the Golden Ratio and harmonic forms (as quoted from Mario Livio’s The Golden Ratio). Why did Luca and Leonardo hide the secret science and mysteries of harmonic forms, and what clues did they provide to deliver a message through time about geometric probabilities in a universe of uncertainty?

It is a story that I will begin to tell, as best as I can imagine, in installments that will be posted on this site every two weeks beginning in April. I invite you to join me, at no cost other than of your time. It is a journey that will reintroduce Luca Pacioli’s account of the power of zero, which is the point of balance between debit and credit where belief is found and from which belief projects through time in the golden ratio of debit and credit. Debit and credit are binary limits, the sum total of any number of which always reconciles to zero in the common functional ground of belief. It is a story of unlimited quantities of binary limits, and the quantum accounting of belief as the singularity that distributes forever in equal and opposite measures owed and received.

The story of Luca and Leonardo is the story of the geometry of time, and if the story resonates in your imagination I will invite if you can afford and desire a contribution that I will forward to the Center for Humane Technology. The Center is a cause to which I have already contributed, and it is my desire that any tokens of belief (that is, money) for the story of quantum accounting and the geometry of time that was devised by Luca and Leonardo be directed to humane causes like the Center. Why? Because the Center is the creation of people who care about the flow of time, people who are beings of matter who long to matter in a way that will benefit all of us. No limit of value can be placed on such worthiness, and it is an honour to spend my time to support their goals.

Image Atributions

De divina proportione – Vigintisex Basium Planum Vacuum by Leonardo da Vinci (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:De_divina_proportione_-_Vigintisex_Basium_Planum_Vacuum.jpg)

Fibonacci Spiral with square sizes up to 34 uploaded to Wikimedia Commons by user: Dicklyon (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fibonacci_spiral_34.svg)

Golden ratio line, Traced by Wikimedia Commons user: Stannered (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Golden_ratio_line.svg)

Illustration 13, from Luca Pacioli’s Divina proportione, by Leonardo da Vinci (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Divina_proportione_-Illustration_13,_crop%26_monochrome.jpg)

La divina proprotione title page, by Luca Pacioli uploaded to Wikimedia Commons from History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries; copyright the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:De_divina_proportione_title_page.png)