It is a little-known fact that the double-entry system of accounting was perfected by a mathematician, Luca Pacioli. This is a brief story of Pacioli’s system, the secret that he embedded in two words, and the meaning of those two words to our own business and the promise we make to our clients.

Already in use by the merchants of Venice and then by many others when Pacioli published the first accounting handbook in 1494, the double-entry system has been at the core of the global economy for hundreds of years. The system generates financial statements that business managers use to measure the progress of their goals, that lenders and investors examine to assess prospects of return on their capital, and on which governments base the calculation of taxes to fund public services.

At first glance, the mathematics involved in Pacioli’s system seem routine.

The account of each transaction between buyer and seller is recorded in two equal parts – one being the source of funds, and its equal and opposite counterpart, the use of funds. Accountants use the word “credit” for the source of funds, and the word “debit” for the use of funds.

In every transaction recorded with the double-entry system, credit = debit and the flow of funds from source to use is measured completely.

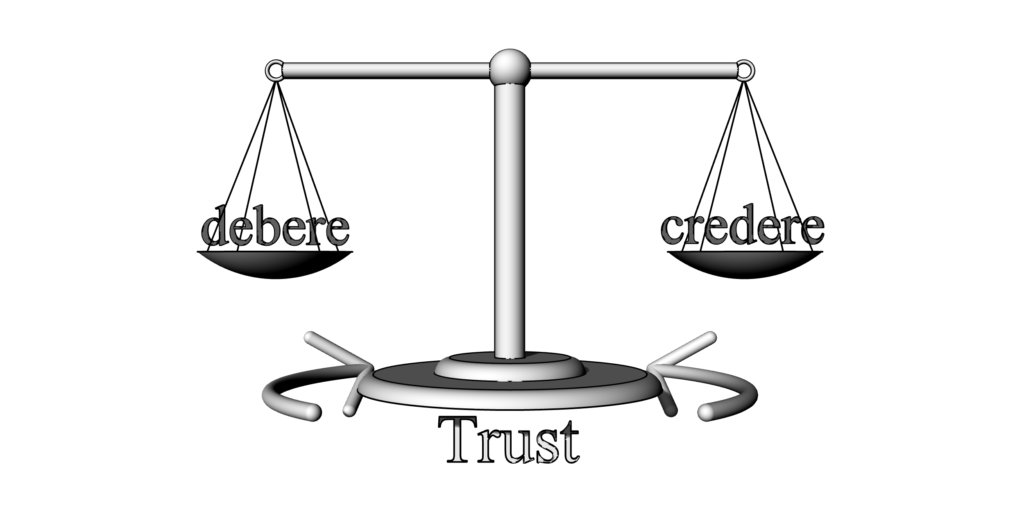

This seems reasonably clear and does not require any advanced mathematics, but the story becomes quite interesting when we reflect on the words that Pacioli chose for the equal and opposite measures of funds in a binary exchange between buyer and seller. Why did he choose the word credit from the Latin credere meaning “belief received”, and the word debit from the Latin debere meaning “belief owed”? What does belief have to do in the exchange of money which is after all what is reported in financial statements?

Let’s pause to consider the story of money:

Is there any intrinsic value in money, or is the value of money derived from the mutual belief that buyer and seller place in it as a medium of exchange? Pacioli proposed that every transaction between buyer and seller is fundamentally an exchange of belief. When we consider the nominal worth of the paper that money is printed on, or the bandwidth that is required for digital currency, we might be inclined to agree with Pacioli’s view about the basis of value of any quantity of money that we exchange in our daily transactions.

The value placed in money, when buyer and seller exchange equal and opposite measures of belief, carries the potential of continuous compounding. This is the power of currency and the belief that it represents. Luca, no doubt, would have found the mathematics of continuous compounding to be intriguing, and isn’t belief in this way the best account we could possibly render? The buyer in one transaction can become the seller in a subsequent exchange, and roles can continue to reverse as belief resonates in its own derivative. The growth of businesses and economies multiplies, with each additional measure of belief exchanged in two equal parts.

The question that remains, however, is what order of credere and debere applied in the very first exchange that was ever measured – was belief received before it was given or was it the other way around? Did the first seller provide goods or services before receiving payment, or did the first buyer provide payment before receiving fair value in exchange?

We many never know the answer with any certainty, but it seems plausible that trust would have been involved. The team at James Myers Professional Corporation know that trust is something that is earned, and our mission is to earn the trust of our clients each day that we provide our time in their service. The belief we receive from our clients is a debt we owe to them, in the same measure.